A Pearl

↧

↧

The Indolence of Decadence - Lowell's Alfred Corning Clark

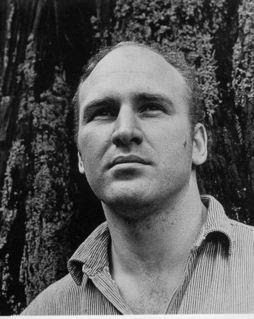

After initially establishing himself at the beginning of his career as a talented poet with a rhetorical style--marked by a dense, rich dose of metaphysical formalism--Robert Lowell "thawed out" in the 1950's, and produced two books leavened with autobiographical detail, and a relaxed manner, which belied the obligations implied in earlier efforts.

Among the poems in the second of those two volumes of verse (Life Studies, 1959 and For the Union Dead, 1964), is this little elegy, notable for its brevity and seeming simplicity. Without knowing more about its subject than what we learn in the poem itself, any reader might suppose that Clark was likely a public figure whom the author had once known in adolescence, one seen rather from afar. The poem's justification, then, would derive either from the depth of grief which the speaker feels, or from the keenness of detail which he uses to evoke his subject, or both.

Alfred Corning Clark (1916-1961)

You read the New York Times

every day at recess,

but in its dry

obituary, a list

of your wives, nothing is news,

except the ninety-five

thousand dollar engagement ring

you gave the sixth.

every day at recess,

but in its dry

obituary, a list

of your wives, nothing is news,

except the ninety-five

thousand dollar engagement ring

you gave the sixth.

Poor rich boy,

you were unseasonably adult

at taking your time,

and died at forty-five.

Poor Al Clark

behind your enlarged,

hardly recognizable photograph,

I feel the pain.

You were alive. You are dead.

You wore bow-ties and dark

blue coats, and sucked

wintergreen or cinnamon lifesavers

to sweeten your breath.

There must be something –

some one to praise

your triumphant diffidence,

your refusal of exertion,

the intelligence

that pulsed in the sensitive,

pale concavities of your forehead.

You never worked,

and were third in the form.

I owe you something –

I was befogged,

and you were too bored,

quick and cool to laugh.

You are dear to me, Alfred;

our reluctant souls united

in our unconventional

illegal games of chess

on the St Mark’s quadrangle.

You usually won –

motionless

as a lizard in the sun.

you were unseasonably adult

at taking your time,

and died at forty-five.

Poor Al Clark

behind your enlarged,

hardly recognizable photograph,

I feel the pain.

You were alive. You are dead.

You wore bow-ties and dark

blue coats, and sucked

wintergreen or cinnamon lifesavers

to sweeten your breath.

There must be something –

some one to praise

your triumphant diffidence,

your refusal of exertion,

the intelligence

that pulsed in the sensitive,

pale concavities of your forehead.

You never worked,

and were third in the form.

I owe you something –

I was befogged,

and you were too bored,

quick and cool to laugh.

You are dear to me, Alfred;

our reluctant souls united

in our unconventional

illegal games of chess

on the St Mark’s quadrangle.

You usually won –

motionless

as a lizard in the sun.

This poem has always resonated for me. Though I was raised on the West Coast, not among the Boston Brahmin culture that was Lowell's birthright, I can still feel the generic sense of loss at hearing of the death of comrades known in youth. The people we had known in childhood, or adolescence, are a select group whose fates are involuntarily bound to ours. There is usually no reason to suppose that we should regard them either as special, or as important, simply on account of the circumstance of our shared ages or condition or proximity. People who become famous may be remembered by those who knew them "when they were unknown" though in the case of very rich, or very talented, individuals, it may become obvious early on, that we will have a reason to remember them eventually.

In the case of Lowell, and Clark, there is the underlying social presumption of privilege. Though Alfred Corning Clark is easily identified, as the grandson (and namesake) of the co-founder of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, there is little detail that I can locate online to flesh out the character Lowell describes in the poem. As scion of one of the great industrial giants' fortunes passed down from the latter half of the 19th Century, Clark's inheritance would have meant he would never have to work, and would bear the burden of that privilege according to his nature.

Formally, the poem employs a simple rough three beat line, essentially prose chopped according to the natural rhythms of phraseology. It's an "easy" poem in that sense, which seems to ask very little in the way of complex comprehension, its ironies held in delicate suspension between simple description and the tantalizing suggestions of ambiguity. Lowell, as an adult, looks both forward from childhood, and back, through the lens of his vicarious adolescent gaze, and his later adult cynicism.

The details we're given--what Clark wore, the bare lineaments of his character, the games of chess that form(ed) the basis of their interaction--would suggest they weren't intimate. Indeed, it is precisely Clark's diffident character ("triumphant"), his refusal of exertion, and an intelligence that "pulsed" in the "pale concavities of [his] forehead . . . too bored, quick and cool to laugh," that the speaker recalls. It is precisely Clark's cool remoteness, his "reluctance" to "unite" even while playing an "unconventional illegal" game of chess, that attracts Lowell. Lowell, the powerfully precocious young poet-to-become, admires Clark's unflappability, his serene assumption of disengagement, without responsibilities, without obligation, without embarrassing passions. Or at least that is how Lowell wishes us to think he feels. It's a strategic choice, one that puts Clark in the cross-hairs of the ironies Lowell can't help expressing.

The details--the wintergreen lifesavers--the "pale concavities"--the "cool" laugh--and that denouement, "motionless as a lizard in the sun"--all suggest a chill, clear as ice, all the controlled reservations of upper class superiority, barren, impotent, remote, selfish, streamlined, decadent, dry, enervated, dull. Yet it's just this emotionally impoverished sterility which inspires the poem.

Elegies may be the occasion for an outpouring of grief, or of amusement, or of rancor. We can't change the past, especially our childhoods, which were the given context of the lives we were born to. We may sense a shared bond that is irresistible, or inescapable, or best ignored and forgotten. In this case, we may feel that Lowell's embrace of his own past, filled with all the complexities of ambiguous affection, embarrassment and pride, is merely symbolized by his eulogy for a childhood companion. We can tell from the way Lowell describes him, that Clark was almost certainly NOT the warm companion we associate with friendship, or shared exploits. The Clark of the poem is someone seen from a little distance, with the same cool detachment that is the central significance of his character. How might Clark have felt about Lowell's version of him?

Alice Darr [nee Alicja Kopzynska]

Interestingly, Clark, whose sixth wife inherited his fortune, had only been married to her for 13 days before "dying in his sleep" of "natural causes" at age 45! That sixth wife, born Alicja Kopzynska [aka: Alicia Darr] in Poland in 1935, had been raised in Lodz, but was allowed to emigrate to the U.S. in 1950 under the so-called Displaced Persons Act. Soon thereafter, Kopzynska's exploits as a notorious playgirl and fortune hunter commenced. Initially linked to young John F. Kennedy, in 1951, with whom she may have become pregnant, she would later be linked socially (and romantically as well) to British actor Edmund Purdom [a British matinee idol specializing in "sword and sandal" epics], to whom she was married (1957-58)--

Edmund Purdom

--as well as Tyrone Power, Richard Beymer, Stewart Wallach, Roberto Rossellini, French guitarist Oliver Despax, James Fox, Omar Sharif, Marco Borghese, Norman Gay (her husband for a time in Nassau), William Holden, Gary Cooper, etc. Following Clark's death, at which point she scored ten million, in addition to a regular $100, 000 annuity pay-out, Darr/Clark would enter the jet set world of European capitols, Caribbean high-life, and engage in numerous affairs and liaisons with the rich and famous, and would make regular notorious mention in the gossip columns of the period. At one point, apparently, J. Edgar Hoover told then Attorney-General Robert F. Kennedy in 1963 that the FBI had information his brother John had paid a $500,000 settlement and had court records sealed in lawsuit brought by a woman who claimed to have been engaged to marry the former President in 1951; allegedly the money was paid to drop the case in 1961; Ms. Darr couldn't be reached for comment. It almost makes one wonder whether Clark's death in 1961 can have been so "natural" after all.

The jet-setter in the Bahamas

Of the previous five wives, I can find nothing online.

The closing picture of Clark, as a "motionless . . . lizard in the sun" has always stayed with me. Lizards are cold-blooded reptiles, which is to say they don't preserve their own body heat, and must soak up heat from the sun by resting outdoors during daytimes.

Lowell's reputation as one of America's best poets has always been somewhat colored by the fact of his presumed "entitlement"--as a function of his having descended from one of the famous "founding families" of New England. It is as if we ought to regard Lowell as having benefited, as an artist, by his associations--male, white, upper class, connected, intellectual, elite, safe, propelled by position and recognition into a natural, if undeserved, advantage.

But people can't choose their inheritance. This is one of the ironies of our politically correct contemporary literary world, that we should demand that our writers and artists reflect the philosophical and religious and sociological pieties of the moment. Yet there is no evidence that the kind of advantage we identify with privilege should ever guarantee genius, or ability, or the effort required to make the best of one's means. Lowell's early work demonstrated that he was first interested in a religious poetry that expressed the conflicts and dilemmas of a tragic world view. It was only later, after he had suffered some serious personal crises, that he undertook to explore his own life in the crucible of his art. And as his reading public came to know, that life was anything but secure. Beset from the beginning by mental demons, difficulties with his parents, conscientious objection and imprisonment, multiple hospitalizations for bi-polar episodes, broken marriages and affairs, lapsed appointments, radical political resistance, etc., Lowell came to see his own artistic life as a public drama carried on in full view of the literary world. But the accomplishments of his work could not be "excused" or "exonerated" by his life. In large measure, he may be said to have "invented" Confessionalism, the literary trope that played such a large part in the poetry of the Sixties, Seventies, and still exerts a powerful influence today in the work of Frederick Seidel, Sharon Olds, among many others. The notion of addressing the facts of one's personal life in poetry in a frank, uncompromising manner has something of the exhibitionistic about it. Personally, I find poetry which does only that, and nothing more, suffers a poverty of invention. But one could never say that of Lowell's work, even when it veered uncomfortably close. The ode to Clark is one example of how a direct response to real personal events, or connections, can be managed, without recourse to mawkish obsequy, or vicarious prurient revelation. I can share Lowell's sadness, at a certain moment in time, without in any way sharing the nature of his grief, no matter how ambiguous it may have been, or how conflicted his expression of it would be. Is wealth or privilege in the possessor prima facie evidence of decadence?

What Lowell seems to be implying is that the qualities which privilege bestows, may be aesthetically inspiring, but still be arid in themselves. The vanity or nonchalant negligence implied by cycling through six marriages may simply be a reflection of individual temperament, rather than an expression of class arrogance. Yet Lowell is able to have it both ways, since the tone of the poem is clearly not slavish, but measured, and deeply ironic in its regard. The speaker is fully implicated in the world he describes, which is what we want from writers. Not the easy condemnation of the smug ideologue, nor pathetic apologetics, but compassion mixed with rueful modesty.

↧

Elephant Panorama

↧

Twin Obituaries

We keep losing people.

That's life.

This last week two poets whom I knew, and had published early in their careers, both died within 48 hours of each other:

Bill Berkson

Blue Is the Hero

Ted Greenwald

Common Sense

Both native New Yorkers. Both men I would not have had the occasion to know, had it not been for our mutual connections to the world of poetry.

Bill died at age 76, Ted at 73.

Ironically, both men suffered from the identical medical condition later in life--lung failure as a result of life-long smoking habit.

It gives me pause to note that. Both my parents were heavy smokers--both two-pack unfiltered Camel people. Our house smelled strongly of tobacco, and I became inured to the smell, and the bad air, as I grew up. Later, when I went back to visit, I was nearly overpowered by the effect. I never smoked. There was nothing about smoking that I saw in their addiction that would have drawn me to the habit. Yet neither died of lung disease, my Stepfather Harry dying in an automobile accident at about age 72, and my mom dying at age 84 from heart failure.

Berkson was heavily identified with Frank O'Hara at the beginning of his career. Bill became the official/unofficial keeper of O'Hara's flame over the years, editing his poetry, tending to his legacy, and moving beyond the association that had been so important to the both of them until the older poet's death in 1966. That was almost 50 years ago, hard to believe. Bill would pursue dual careers in poetry and art criticism in his later adult life, both successfully. Sophisticated, cosmopolitan, charming, confident, witty, and generous--an impressive man.

Ted Greenwald, a confirmed and unashamed devoted New Yorker, was a much less visible cultural figure, without Bill's social connections and background. There was something essentially genuine about his "working clothes" approach to poetry and to his life. I like to think of him as an "urban primitive" who spoke the language of the street, but knew his art inside and out.

My contact with these men over the years would hardly suggest we were close. But I always felt a kinship with them, and the deeper implications of what their respective artistic investigations and commitments stood for.

I live in earthquake country, right on top of the fault line, and in the middle of a notorious slide zone. You never know when the earth might just start jiggling and shifting under the your feet.

The death of these two men is a seismic shift in my life. Things will never be the same again.

↧

On the Seventh Day of Summer

On the seventh day of Summer, my true love gave to me . . .

a new cocktail recipe!

Summer is here, and everyone is floating along in oblivious continuity. Going about their business as if nothing had happened, working, sleeping, recreating, marrying, having babies, buying groceries, taking out the garbage, petting dogs, and generally staying out of mischief.

As I near old age, I keep having the rather unpleasant sense that some of the things I've done in the past, and may do again in the future, might be the "last time" I do them. This sense of unrepeatability is disquieting. I like reliable things as much or more than new things, and the thought that my next trip fly-fishing, or my next trip photographing the landscape, might be my last, is one of the liabilities of self-knowledge, or self-consciousness--something we possess that most animals don't.

They say elephants mourn the loss of one of their tribe, and will even return to a place where one had died, to pay their respects, and share a feeling of grief. Elephants are also said to have long memories--another human trait. As I get older, some of the things I had not thought about for half a century, come back to me, unannounced, evoking feelings of regret or minor joy. More and more, I realize that I am the only surviving keeper of these memories, and that when I go, there will no longer be a surviving witness.

I remember one day, perhaps 60+ years ago, when my parents and I went picnicking up on the Russian River--to a little place called Cazadero, on Austin Creek. In those days, people simply parked along the road and walked down to the water. On this day, I remember my Step-dad (whom I didn't know was not my "real" father yet) had persuaded my Mom to wear her bathing suit. Mom wasn't the outdoor type, and not the swimming type, and not the exhibitionist type either. I can still recall her tiptoeing across the rock shore, complaining about being cold, the sharp stones hurting her feet, refusing all appeals to come into the water, and generally just shivering and complaining. I can recall the green and white flower material of her suit, and how pale she was. The moment seems emblematic of my parents' relationship--how split their characters were, and how little they shared: Mom the indoors type, quiet, sedentary, Dad the outdoorsman, active, forthright. The thing is, I'm the only one who remembers this, and, like all the other memories locked in my head, it will fade into nothingness when I go. If my Mom were still alive today (she'd be 91 if she were) I'm sure she'd remember that day, just as I have, and it would be something we could share. But she's gone, and there's no one else in the universe who can confirm and tally what I've just described. I don't know why that should trouble me, except that such memories do matter to me. They comprise the pictures I have of my own past, which is not only rapidly receding from me, but from the history of my time.

But this is the seventh day of Summer, and what better time to evoke memories, or to create new ones, than by toasting them with a novel new libation?!

2 parts dry vermouth

2 parts white rum

1 part st. germaine

2/3 part yellow chartreuse

1 part fresh lime juice

Shaken vigorously and poured into well-chilled cocktail glasses (makes 2).

It's guaranteed to appeal to drinkers and non-drinkers alike, so have no fear of inebriation. One cocktail never killed anyone, though two might be inadvisable without a chauffeur.

↧

↧

Creeley's Oppen

I've written previously about George Oppen's Discrete Series, in a blogpost here under Minimalism Part IV, on July 30, 2009. As an example of an approach to verse that employed a reductive, spare concision to convey unusual effects, it has always struck me as an ideal example of the form. I loved that book, long before I knew the back-story of its composition and publication, and appreciated its value without realizing the context of its initial emphasis, or why it would eventually become symbolic in its temporal isolation in the middle of the 1930's.

I recently came upon a copy of Oppen's Selected Poems [New Directions, 2003], edited by Robert Creeley, with a Chronology of Oppen's life by Rachel Blau DuPlessis, a book which for reasons I can't explain I'd never seen before. Published well after Oppen [1908-1984] had died, it's a telling, though perhaps unintentional, piece of evidence about how Creeley saw the elder poet, a figure who had explored some of the same literary territory that the younger man would, thirty years later.

As the Chronology makes clear, Oppen's earlier life was unusual in a number of ways. Born into a comparatively well-off Jewish family, his Mother committed suicide when George was only a toddler. Early difficulties in school lead to a restless youth, and much travel. While still in his 'teens, he meets and marries Mary, his life-companion, and together they commit to political principles that align them with the Communist Party, which they join in 1935, becoming active in union organizing and relief efforts.

A young Oppen with the wife Mary

Creeley, born in 1926, is only 9 when Discrete Series is published in 1935. Oppen is a full generation older than Creeley. According to the Chronology, Oppen had virtually completed the book by 1930, when he was just 22. Discrete Series, then, is in fact a very young man's book, written at the end of the 1920's, just before the Wall Street Crash, at the beginning of the Depression, by a man whose political sympathies are, from an early age, Left. The young author decides at this key juncture, that the artistic life must be set aside, in favor of social awareness and action, and by the beginning of the War, he is working in an automobile factory in Detroit. Drafted into the Army, he serves in Europe where he is severely wounded in the field, and leaves the service a highly decorated veteran. During the early 'Fifties, he comes under pressure from the FBI for his political activity, and decides to live in Mexico. The Oppens don't return to the U.S. until 1960, when he begins once again to take up his pen. In close succession, he publishes three books of poems [The Materials, 1962; This in Which, 1965; and Of Being Numerous, 1968]. This outpouring of work (he wins the Pulitzer for the third book) leads to a general recognition by a new generation of readers, who for the most part are unaware of the author's earlier incarnation as a 'Thirties activist. Though the first book is reprinted in 1966, the context of its original appearance, and the meaning of the long hiatus of publication, remain largely unknown.

It would take a whole book-length study even to outline the literary developments which occur between 1935 and 1960, but suffice it to say that how Oppen's work was initially viewed during the 1960's, and later, must be understood as a part of a larger struggle taking place in American art and literature, between the Depression, and the beginning of the 1960's. Oppen's "underground" self-exile and prohibition effectively removes him from the time-line for 20 years, a period during which socialism is rejected, the country fights and wins a world war, then undergoes a tortuous period of anxiety and paranoia (The McCarthy Era), while experiencing its period of greatest broad economic prosperity.

In the meantime, Creeley, who comes of age as a writer during the notoriously quiet and tradition-bound 1950's, begins to achieve recognition and success at precisely the same time as the "later" Oppen. Their respective careers run parallel through the 1960's and 1970's, each participating in what we now understand as the period of the New American Poetry, initiated by the publication of the anthology of that name [Grove Press, 1960] edited by Donald Allen. Ironically, Oppen cannot be included in that selection, because he hasn't yet written the poems that will place him among its company!

Greeley older

Creeley younger

For Creeley, Objectivism was an historical artifact, whose causes and concerns had faded from memory. Like Oppen's first readers in the 1960's, he understood the older writer as a survivor from an earlier period, recollecting those life-experiences in a calm, meditative style. The marked differences between the method of the poems in Discrete Series and those written after about 1958, suggest not just the transformations wrought by time, but an aesthetic about-face which undercuts the meaning and value of the earlier work. The divide between the earlier and later Oppen isn't linear, following the clear descent from a sharp eye to a thoughtful reappraisal, but a reemergence from nearly total obscurity.

Oppen older

Turning to Creeley's selections, it is astonishing to see that he chooses only two poems from Discrete Series--"The knowledge not of sorrow, you were" and "The edge of the ocean"--as if that earlier volume were an afterthought, only to be remarked with a couple of small snapshots for the family album. Why, one might ask, would Creeley's appreciation of Oppen be so narrowly focused on the later writer, instead of upon the youthful (30 years earlier) revolutionary of 1928?

The 1st Edition of Discrete Series

It's intriguing to wonder why Creeley would choose to de-emphasize the older Oppen in favor of the later. Perhaps it's because he felt that the issues and concerns of the earlier writer were no longer pertinent to a later audience. Perhaps those early, "objectivist" priorities (sincerity and objectification) were no longer valid measures. Oppen had said "a discrete series is a series of terms each of which is empirically derived, each one of which is empirically true. And this is the reason for the fragmentary character of those poems [in Discrete Series]." It's instructive to place the poems in Discrete Series beside those of Creeley during his own "minimalist" phase--Pieces [Scribner's, 1969]. There can be no doubt that Creeley's indulgence in the minimalist form is parallel to Oppen's, yet there are clear differences in style and approach. While Oppen's poems are "fragmentary" and use parataxis freely, Creeley's are invariably grammatical and even narrative in progression, frequently reducing poems down to singular grammatical units, but never breaking them apart. Oppen's poems in Discrete Series are rather molecular, while Creeley's are constructive, using what lies to hand.

Did Creeley's de-emphasis of the earlier Oppen also signal a political dismissal? It's a question that I leave open for the time being. I can only say that it's strange that he would choose fully 44 pages of work from the end of Oppen's career (the poems from Seascape: Needle's Eye [1972]; Myth of the Blaze [1975]; and Primitive [1978]), reprinting only two poems (two pages) from Discrete Series. In my view, the poems in Discrete Series are not merely stronger than nearly everything he published later, they are so much more original than anything that had come before, and driven by a vision which is so much clearer and and better defined than the poems after 1958, there is hardly any comparison.

If we wanted to write the alternative literary history of America, we would certainly have to mark the publication of Discrete Series in 1935 as among a handful of signal events, many times more vital and predictive of later developments, than anything that was being done at the time. Perhaps the point is that Oppen's earlier book had been so thoroughly effaced from literary consciousness that its discoveries and explorations would have to be completely reinvented by writers such as Eigner, Creeley, and others of the post-War generation; as if--as if!--Discrete Series had never happened! It is almost as if Creeley's deliberate suppression of that work were a new kind of repudiation of an earlier exploration and accomplishment--not on political grounds, but on aesthetic ones.

The self-abnegation implied by Oppen's abandonment of verse as a kind of irresponsible activity in face of widespread social distress, is matched by the chastening after-effects of political suppression following the McCarthy Era. It is possible, perhaps, to deliberately "forget" the unfortunate events of a generation or two back--and the part played in them by active participants--but the written artifacts can't be so easily set aside. Creeley sees Discrete Series through the wrong end of his telescope, and judges it to have been unformed and relatively minor.

Why is it that each generation tends to see the efforts of preceding ranks as the work of "old men"--and not the vigorous, hopeful, brave experiments of young men, just starting out, fresh and untamed, unswayed by caution, or fear of rejection?

Discrete Series is the writing of a very young man. That tells us a great deal about the work, and about those who do or don't care to acknowledge the fact.

↧

When To Cut Your Losses

In the Bay Area, we have the luxury of two major league baseball franchises--the San Francisco Giants, and the Oakland Athletics.

Over the last several years, these respective teams have pursued very different management strategies, with respect to how they construct their rosters from year to year.

The A's have become notorious for a constantly shifting roster re-build, dumping half or more of each year's players through trades or voluntary releases, to such a degree that fans feel as if they must be "introduced" to an entirely new squad each spring training. This approach de-emphasizes "loyalty" and team cohesion in favor of hard pragmatic measures; it's run like a corporation, hiring and firing willfully, without regarding for the feelings of individual players, or of fan sentiment. Players who do very well or very poorly, are likely to be treated the same, either to rid the team of their salary commitment, or because of poor performance. Players aren't people in this system. They're just ciphers or parts of a machine. The system places great emphasis on the skill and intuition of the general manager, which is why the team general manager, Billy Beane, has been lionized by the media (and even a major Hollywood film based on a book about him and his management style) for his "moneyball" success in crafting competitive teams.

The Giants, on the other hand, have built a successful franchise on a different principle. Brian Sabean, the Giants General Manager from 1996 to 2015, took a different approach, building teams through the minor league system, sticking with them through the early times as they matured, and through shrewd judgment of existing free agent talent. The team has attempted to treat its players as the emotional, sensitive people they are, valuing individual player loyalty, and nurturing team cohesion. This approach has brought the team three world championships in the last five years, and the team is comfortably, at this writing, in first place in the NL West Division, also leading the majors in winning during much of the last month or so.

But there are problems to both approaches. The Athletics are ruthless in dealing with talent. Professional major league teams are businesses. If a team isn't performing, it must be regarded dispassionately, the bad (or weakly performing) parts cut out, and replaced with better options. There's a certain amount of fluidity to that, of course, since all players, and all groups of players, undergo fluctuations from day to day, week to week, and month to month. The Giants, on the other hand, seem to over-emphasize player loyalty, often holding onto a player well after that player has demonstrated a decline in quality--an inevitable factor in almost all players' careers.

Tim Lincecum displayed Cy Young numbers for five years (2007-2011, during which his combined record was 69-41), but then his career began to tank. This was obvious for anyone to see. His herky-jerky motion, relatively small frame wasn't constructed for a long career. He lost velocity on his fast-ball, and began to lose his control. The handwriting was on the wall. Lincecum's career was destined to be a short one, as I had predicted way back in 2010 here on The Compass Rose. Yet the Giants held on to him, despite this decline, partly out of a sense of sentiment (or nostalgia).

Matt Cain came up through the Giants farm system, and became what is commonly called a "good journeyman" position on the staff, going 85-78 between 2005 and 2012. Then, almost overnight, his arm went bad, and his participation was cut in half. It was clear, by 2014, that Cain was no longer the strong, young journeyman he'd once been, as his ERA ramped up, and hitters began teeing off on his diminished stuff. He underwent arm surgery, and his return has been a disaster. Cain's career is over, but the team seems determined not to accept that verdict.

The team has had similar experiences with free agent hurlers. Tim Hudson was clearly over the hill, whose best years, with Oakland, and then, for several years, the Atlanta Braves. Yet the Giants hired him for two seasons, during which his combined record was 17-22.

In 2014, the Giants signed Jake Peavy to a three-year contract, despite his going 1-9 for the Red Sox the first half of that year. Peavy's best days had been with San Diego, where he went 86-62, and earned a Cy Young with 19 wins in 2007. Judging from how he's pitched since then, there's no evidence that he has the body or the skill to put up numbers resembling those ever again.

The Giants have been through this routine before with Barry Zito, their worst free agent signing ever. 63-69 in the seven seasons of his long contract. Though it was clear that Zito's career was essentially in disarray by 2008, the team kept using him--and losing with him--through another four agonizing years of frustration.

Contracts and obligations often weigh teams down. Players given huge long-term contracts may prove to have been very bad investments. Giving up on a player in mid-career may sometimes be a mistake, though a simple change of scene may be the only way of reviving a player's performance. Astute students of the game can usually tell who to offer the big contracts to. But letting emotion and sentiment dictate your moves can be a mistake.

Right now, the Giants have three very good starters in Bumgarner, Cueto and Samardzija. But Peavy and Cain are dragging the team down. Any game that either of these two guys start is likely to be a blow-out loss. Neither seems capable of sustaining more than an inning or two of acceptable dominance, frequently giving up runs in bunches, often to mediocre teams. As long as the Giants keep running these guys out there, we're going to have to keep crossing our fingers. It's like expecting that 40% of your games will be forfeits!

It would be nice if a faith in players earned dividends in the real world. But in professional sports, the bottom line is made from ability and success. Players whose abilities have withered, can't be kept around just "for old times' sake." These two has-beens need to be shown the door, and replacements found. I'm all for loyalty and humanity and common decency, but Peavy and Cain are no longer major league pitchers. It's over. Better to cut the cord now, before they drag the team down in the standings.

I'm not suggesting that the Giants should be run like the A's. Quite the opposite. Building strong teams is nearly impossible by turning over your whole roster every years--and the effects on your fan base are disastrous. But I do think the Giants need to be more realistic about these tired old arms than they have been. The team is in contention for another title this year. The Cubs, who are trying to win it all this time, after a century of frustration, would be unlikely to settle for second-rate performance like that we've been getting from Peavy and Cain. We should be just as impatient.

↧

When To Cut Your Losses

In the Bay Area, we have the luxury of two major league baseball franchises--the San Francisco Giants, and the Oakland Athletics.

Over the last several years, these respective teams have pursued very different management strategies, with respect to how they construct their rosters from year to year.

The A's have become notorious for a constantly shifting roster re-build, dumping half or more of each year's players through trades or voluntary releases, to such a degree that fans feel as if they must be "introduced" to an entirely new squad each spring training. This approach de-emphasizes "loyalty" and team cohesion in favor of hard pragmatic measures; it's run like a corporation, hiring and firing willfully, without regarding for the feelings of individual players, or of fan sentiment. Players who do very well or very poorly, are likely to be treated the same, either to rid the team of their salary commitment, or because of poor performance. Players aren't people in this system. They're just ciphers or parts of a machine. The system places great emphasis on the skill and intuition of the general manager, which is why the team general manager, Billy Beane, has been lionized by the media (and even a major Hollywood film based on a book about him and his management style) for his "moneyball" success in crafting competitive teams.

The Giants, on the other hand, have built a successful franchise on a different principle. Brian Sabean, the Giants General Manager from 1996 to 2015, took a different approach, building teams through the minor league system, sticking with them through the early times as they matured, and through shrewd judgment of existing free agent talent. The team has attempted to treat its players as the emotional, sensitive people they are, valuing individual player loyalty, and nurturing team cohesion. This approach has brought the team three world championships in the last five years, and the team is comfortably, at this writing, in first place in the NL West Division, also leading the majors in winning during much of the last month or so.

But there are problems to both approaches. The Athletics are ruthless in dealing with talent. Professional major league teams are businesses. If a team isn't performing, it must be regarded dispassionately, the bad (or weakly performing) parts cut out, and replaced with better options. There's a certain amount of fluidity to that, of course, since all players, and all groups of players, undergo fluctuations from day to day, week to week, and month to month. The Giants, on the other hand, seem to over-emphasize player loyalty, often holding onto a player well after that player has demonstrated a decline in quality--an inevitable factor in almost all players' careers.

Tim Lincecum displayed Cy Young numbers for five years (2007-2011, during which his combined record was 69-41), but then his career began to tank. This was obvious for anyone to see. His herky-jerky motion, relatively small frame wasn't constructed for a long career. He lost velocity on his fast-ball, and began to lose his control. The handwriting was on the wall. Lincecum's career was destined to be a short one, as I had predicted way back in 2010 here on The Compass Rose. Yet the Giants held on to him, despite this decline, partly out of a sense of sentiment (or nostalgia).

Matt Cain came up through the Giants farm system, and became what is commonly called a "good journeyman" position on the staff, going 85-78 between 2005 and 2012. Then, almost overnight, his arm went bad, and his participation was cut in half. It was clear, by 2014, that Cain was no longer the strong, young journeyman he'd once been, as his ERA ramped up, and hitters began teeing off on his diminished stuff. He underwent arm surgery, and his return has been a disaster. Cain's career is over, but the team seems determined not to accept that verdict.

The team has had similar experiences with free agent hurlers. Tim Hudson was clearly over the hill, whose best years had been with Oakland, and then, for several years, the Atlanta Braves. Yet the Giants hired him for two seasons, during which his combined record was 17-22. In retrospect, that decision looks to have been a mistake, unless you accept the pragmatic notion that every staff must have a few "innings-eaters" even if their starts result in losses.

In 2014, the Giants signed Jake Peavy to a three-year contract, despite his going 1-9 for the Red Sox the first half of that year. Peavy's best days had been with San Diego, where he went 86-62, and earned a Cy Young with 19 wins in 2007. Judging from how he's pitched since then, there's no evidence that he has the body or the skill to put up numbers resembling those ever again.

The Giants have been through this routine before with Barry Zito, their worst free agent signing ever. 63-69 in the seven seasons of his long contract. Though it was clear that Zito's career was essentially in disarray by 2008, the team kept using him--and losing with him--through another four agonizing years of frustration.

Contracts and obligations often weigh teams down. Players given huge long-term contracts may prove to have been very bad investments. Giving up on a player in mid-career may sometimes be a mistake, though a simple change of scene may be the only way of reviving a player's performance. Astute students of the game can usually tell who to offer the big contracts to. But letting emotion and sentiment dictate your moves can be a mistake.

Right now, the Giants have three very good starters in Bumgarner, Cueto and Samardzija. But Peavy and Cain are dragging the team down. Any game that either of these two guys start is likely to be a blow-out loss. Neither seems capable of sustaining more than an inning or two of acceptable dominance, frequently giving up runs in bunches, often to mediocre teams. As long as the Giants keep running these guys out there, we're going to have to keep crossing our fingers. It's like expecting that 40% of your games will be forfeits!

It would be nice if a faith in players earned dividends in the real world. But in professional sports, the bottom line is made from ability and success. Players whose abilities have withered, can't be kept around just "for old times' sake." These two has-beens need to be shown the door, and replacements found. I'm all for loyalty and humanity and common decency, but Peavy and Cain are no longer major league pitchers. It's over. Better to cut the cord now, before they drag the team down in the standings.

I'm not suggesting that the Giants should be run like the A's. Quite the opposite. Building strong teams is nearly impossible by turning over your whole roster every years--and the effects on your fan base are disastrous. But I do think the Giants need to be more realistic about these tired old arms than they have been. The team is in contention for another title this year. The Cubs, who are trying to win it all this time, after a century of frustration, would be unlikely to settle for second-rate performance like that we've been getting from Peavy and Cain. We should be just as impatient.

↧

When To Cut Your Losses

In the Bay Area, we have the luxury of two major league baseball franchises--the San Francisco Giants, and the Oakland Athletics.

Over the last several years, these respective teams have pursued very different management strategies, with respect to how they construct their rosters from year to year.

The A's have become notorious for a constantly shifting roster re-build, dumping half or more of each year's players through trades or voluntary releases, to such a degree that fans feel as if they must be "introduced" to an entirely new squad each spring training. This approach de-emphasizes "loyalty" and team cohesion in favor of hard pragmatic measures; it's run like a corporation, hiring and firing willfully, without regarding for the feelings of individual players, or of fan sentiment. Players who do very well or very poorly, are likely to be treated the same, either to rid the team of their salary commitment, or because of poor performance. Players aren't people in this system. They're just ciphers or parts of a machine. The system places great emphasis on the skill and intuition of the general manager, which is why the team general manager, Billy Beane, has been lionized by the media (and even a major Hollywood film based on a book about him and his management style) for his "moneyball" success in crafting competitive teams.

The Giants, on the other hand, have built a successful franchise on a different principle. Brian Sabean, the Giants General Manager from 1996 to 2015, took a different approach, building teams through the minor league system, sticking with them through the early times as they matured, and through shrewd judgment of existing free agent talent. The team has attempted to treat its players as the emotional, sensitive people they are, valuing individual player loyalty, and nurturing team cohesion. This approach has brought the team three world championships in the last five years, and the team is comfortably, at this writing, in first place in the NL West Division, also leading the majors in winning during much of the last month or so.

But there are problems to both approaches. The Athletics are ruthless in dealing with talent. Professional major league teams are businesses. If a team isn't performing, it must be regarded dispassionately, the bad (or weakly performing) parts cut out, and replaced with better options. There's a certain amount of fluidity to that, of course, since all players, and all groups of players, undergo fluctuations from day to day, week to week, and month to month. The Giants, on the other hand, seem to over-emphasize player loyalty, often holding onto a player well after that player has demonstrated a decline in quality--an inevitable factor in almost all players' careers.

Tim Lincecum displayed Cy Young numbers for five years (2007-2011, during which his combined record was 69-41), but then his career began to tank. This was obvious for anyone to see. His herky-jerky motion, relatively small frame wasn't constructed for a long career. He lost velocity on his fast-ball, and began to lose his control. The handwriting was on the wall. Lincecum's career was destined to be a short one, as I had predicted way back in 2010 here on The Compass Rose. Yet the Giants held on to him, despite this decline, partly out of a sense of sentiment (or nostalgia).

Matt Cain came up through the Giants farm system, and became what is commonly called a "good journeyman" position on the staff, going 85-78 between 2005 and 2012. Then, almost overnight, his arm went bad, and his participation was cut in half. It was clear, by 2014, that Cain was no longer the strong, young journeyman he'd once been, as his ERA ramped up, and hitters began teeing off on his diminished stuff. He underwent arm surgery, and his return has been a disaster. Cain's career is over, but the team seems determined not to accept that verdict.

The team has had similar experiences with free agent hurlers. Tim Hudson was clearly over the hill, whose best years had been with Oakland, and then, for several years, the Atlanta Braves. Yet the Giants hired him for two seasons, during which his combined record was 17-22. In retrospect, that decision looks to have been a mistake, unless you accept the pragmatic notion that every staff must have a few "innings-eaters" even if their starts result in losses.

In 2014, the Giants signed Jake Peavy to a three-year contract, despite his going 1-9 for the Red Sox the first half of that year. Peavy's best days had been with San Diego, where he went 86-62, and earned a Cy Young with 19 wins in 2007. Judging from how he's pitched since then, there's no evidence that he has the body or the skill to put up numbers resembling those ever again.

The Giants have been through this routine before with Barry Zito, their worst free agent signing ever. 63-69 in the seven seasons of his long contract. Though it was clear that Zito's career was essentially in disarray by 2008, the team kept using him--and losing with him--through another four agonizing years of frustration.

Contracts and obligations often weigh teams down. Players given huge long-term contracts may prove to have been very bad investments. Giving up on a player in mid-career may sometimes be a mistake, though a simple change of scene may be the only way of reviving a player's performance. Astute students of the game can usually tell who to offer the big contracts to. But letting emotion and sentiment dictate your moves can be a mistake.

Right now, the Giants have three very good starters in Bumgarner, Cueto and Samardzija. But Peavy and Cain are dragging the team down. Any game that either of these two guys start is likely to be a blow-out loss. Neither seems capable of sustaining more than an inning or two of acceptable dominance, frequently giving up runs in bunches, often to mediocre teams. As long as the Giants keep running these guys out there, we're going to have to keep crossing our fingers. It's like expecting that 40% of your games will be forfeits!

It would be nice if a faith in players earned dividends in the real world. But in professional sports, the bottom line is made from ability and success. Players whose abilities have withered, can't be kept around just "for old times' sake." These two has-beens need to be shown the door, and replacements found. I'm all for loyalty and humanity and common decency, but Peavy and Cain are no longer major league pitchers. It's over. Better to cut the cord now, before they drag the team down in the standings.

I'm not suggesting that the Giants should be run like the A's. Quite the opposite. Building strong teams is nearly impossible by turning over your whole roster every year--and the effects on your fan base are disastrous. But I do think the Giants need to be more realistic about these tired old arms than they have been. The team is in contention for another title this year. The Cubs, who are trying to win it all this time, after a century of frustration, would be unlikely to settle for second-rate performance like that we've been getting from Peavy and Cain. We should be just as impatient.

↧

↧

The Updated Gimlet

Here's a small departure from tradition in the form of an augmented Gimlet.

The Gimlet, according to a 1953 Raymond Chandler novel The Long Goodbye, is half gin and half Rose's lime juice. And what better authority could there be?

The point of the traditional Gimlet is lime, and I wouldn't argue with that. It's simple and to the point. Give the gin a little fillip of dry citrus and nothing more.

But who can leave well enough alone? We can have a traditional Gimlet anytime, but that doesn't mean we can't fiddle with it a little, no?

So, perusing my liquor cabinet, I thought: Why not replace the lime with lemon, and try adding something allied, but mysterious, to the combination?

The combination below is intriguing.

3 Parts Boodles gin

2/3 part limoncello (lemon liquor)

2/3 part Cotton Candy liquor

Well shaken, and served up in frosted cocktail glass with a thin

Lime wedge garnish

A traditional Gimlet will look slightly yellowish, from the lime juice. This version is just a tiny bit warmer in tint, since the Cotton Candy liquor is pink.

The flavor is clear lime-like, but mysterious and subtle. Light, and evanescent.

↧

Creeley's Oppen

I've written previously about George Oppen's Discrete Series, in a blogpost here under Minimalism Part IV, on July 30, 2009. As an example of an approach to verse that employed a reductive, spare concision to convey unusual effects, it has always struck me as an ideal example of the form. I loved that book, long before I knew the back-story of its composition and publication, and appreciated its value without realizing the context of its initial emphasis, or why it would eventually become symbolic in its temporal isolation in the middle of the 1930's.

I recently came upon a copy of Oppen's Selected Poems [New Directions, 2003], edited by Robert Creeley, with a Chronology of Oppen's life by Rachel Blau DuPlessis, a book which for reasons I can't explain I'd never seen before. Published well after Oppen [1908-1984] had died, it's a telling, though perhaps unintentional, piece of evidence about how Creeley saw the elder poet, a figure who had explored some of the same literary territory that the younger man would, thirty years later.

As the Chronology makes clear, Oppen's earlier life was unusual in a number of ways. Born into a comparatively well-off Jewish family, his Mother committed suicide when George was only a toddler. Early difficulties in school lead to a restless youth, and much travel. While still in his 'teens, he meets and marries Mary, his life-companion, and together they commit to political principles that align them with the Communist Party, which they join in 1935, becoming active in union organizing and relief efforts.

A young Oppen with the wife Mary

Creeley, born in 1926, is only 9 when Discrete Series is published in 1935. Oppen is a full generation older than Creeley. According to the Chronology, Oppen had virtually completed the book by 1930, when he was just 22. Discrete Series, then, is in fact a very young man's book, written at the end of the 1920's, just before the Wall Street Crash, at the beginning of the Depression, by a man whose political sympathies are, from an early age, Left. The young author decides at this key juncture, that the artistic life must be set aside, in favor of social awareness and action, sets aside writing altogether, and by the beginning of the War, he is working in an automobile factory in Detroit. Drafted into the Army, he serves in Europe where he is severely wounded in the field, and leaves the service a highly decorated veteran. During the early 'Fifties, he comes under pressure from the FBI for his political activity, and decides in 1950 to live in Mexico. The Oppens don't return to the U.S. until 1960, when he begins once again to take up his pen. In close succession, he publishes three books of poems [The Materials, 1962; This in Which, 1965; and Of Being Numerous, 1968]. This outpouring of work (he wins the Pulitzer for the third book) leads to a general recognition by a new generation of readers, who for the most part are unaware of the author's earlier incarnation as a 'Thirties activist. Though the first book is reprinted in 1966, the context of its original appearance, and the meaning of the long hiatus of publication, remain largely unknown.

It would take a whole book-length study even to outline the literary developments which occur between 1935 and 1960, but suffice it to say that how Oppen's work was initially viewed during the 1960's, and later, must be understood as a part of a larger struggle taking place in American art and literature during this period, between the Depression and the beginning of the 1960's. Oppen's "underground" self-exile and prohibition effectively removes him from the time-line for 20 years, a period during which socialism is rejected, the country fights and wins a world war, then undergoes a tortuous period of anxiety and paranoia (The McCarthy Era), while experiencing its period of greatest broad economic prosperity.

In the meantime, Creeley, who comes of age as a writer during the notoriously quiet and tradition-bound 1950's, begins to achieve recognition and success at precisely the same time as the "later" Oppen. Their respective careers run parallel through the 1960's and 1970's, each participating in what we now understand as the period of the New American Poetry, initiated by the publication of the anthology of that name [Grove Press, 1960] edited by Donald Allen. Ironically, Oppen cannot be included in that selection, because he hasn't yet written the poems that will place him among its company!

Greeley older

Creeley younger

For Creeley, Objectivism was an historical artifact, whose causes and concerns had faded from memory. Like Oppen's first readers in the 1960's, he understood the older writer as a survivor from an earlier period, recollecting those life-experiences in a calm, meditative style. The marked differences between the method of the poems in Discrete Series and those written after 1958, suggest not just the transformations wrought by time, but an aesthetic about-face which undercuts the meaning and value of the earlier work. The divide between the earlier and later Oppen isn't linear, following the clear descent from a sharp eye to a thoughtful reappraisal, but a reemergence from nearly total obscurity.

Oppen older

Turning to Creeley's selections, it is astonishing to see that he chooses only two poems from Discrete Series--"The knowledge not of sorrow, you were" and "The edge of the ocean"--as if that earlier volume were an afterthought, only to be remarked with a couple of small snapshots for the family album. Why, one might ask, would Creeley's appreciation of Oppen be so narrowly focused on the later writer, instead of upon the youthful (30 years earlier) revolutionary of 1928?

The 1st Edition of Discrete Series

It's intriguing to wonder why Creeley would choose to de-emphasize the younger Oppen in favor of the later. Perhaps it's because he felt that the issues and concerns of the earlier writer were no longer pertinent to a later audience. Perhaps those early, "objectivist" priorities (sincerity and objectification) were no longer valid measures. Oppen had said (in retrospect) "a discrete series is a series of terms each of which is empirically derived, each one of which is empirically true. And this is the reason for the fragmentary character of those poems [in Discrete Series]." It's instructive to place the poems in Discrete Series beside those of Creeley during his own "minimalist" phase--Pieces [Scribner's, 1969]. There can be no doubt that Creeley's indulgence in the minimalist form is parallel to Oppen's, yet there are clear differences in style and approach. While Oppen's poems are "fragmentary" and use parataxis freely, Creeley's are invariably grammatical and even narrative in progression, frequently reducing poems down to singular grammatical units, but never breaking them apart. Oppen's poems in Discrete Series are rather molecular, while Creeley's are constructive, using what lies to hand.

Did Creeley's de-emphasis of the earlier Oppen also signal a political dismissal? It's a question that I leave open for the time being. I can only say that it's strange that he would choose fully 44 pages of work from the end of Oppen's career (the poems from Seascape: Needle's Eye [1972]; Myth of the Blaze [1975]; and Primitive [1978]), reprinting only two poems (two pages) from Discrete Series. In my view, the poems in Discrete Series are not merely stronger than nearly everything he published later; they are so much more original than anything that had come before, and driven by a vision which is so much clearer and and better defined than the poems after 1958, there is hardly any comparison.

If we wanted to write the alternative literary history of America, we would certainly have to mark the publication of Discrete Series in 1935 as among a handful of signal events, many times more vital and predictive of later developments, than anything else that was being done at the time. Perhaps the point is that Oppen's earlier book had been so thoroughly effaced from literary consciousness that its discoveries and explorations would have to be completely reinvented by writers such as Eigner, Creeley, and others of the post-War generation; as if--as if!--Discrete Series had never happened! It is almost as if Creeley's deliberate suppression of that work were a new kind of repudiation of an earlier exploration and accomplishment--not on political grounds, but on aesthetic ones.

The self-abnegation implied by Oppen's abandonment of verse as a kind of irresponsible activity in face of widespread social distress, is matched by the chastening after-effects of political suppression following the McCarthy Era. It is possible, perhaps, to deliberately "forget" the unfortunate events of a generation or two back--and the part played in them by active participants--but the written artifacts can't be so easily set aside. Creeley sees Discrete Series through the wrong end of his telescope, and judges it to have been unformed and relatively minor.

Why is it that each generation tends to see the efforts of preceding ranks as the work of "old men"--and not the vigorous, hopeful, brave experiments of young men, just starting out, fresh and untamed, unswayed by caution, or fear of rejection?

Discrete Series is the writing of a very young man. That tells us a great deal about the work, and about those who do or don't care to acknowledge the fact.

↧

The Permission of The Meadow: Duncan's "Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow"

Though I have never been a great fan of Duncan's work, there are a handful of his poems which I feel belong among the best poems of the 20th Century. "My Mother Would Be Falconress" would be one, and another, the first poem in his collection The Opening of the Field [Grove Press, 1960] below--are two such. As you will note, the evident title is grammatically the first line of the poem, an affectation that I find interesting, as if the music of the title were subsumed into the lyrics of the whole poem, rather than being a separate announcement of its subject-matter or content. The title thus acquires a refrain-like familiarity which it would not otherwise have.

Duncan's childhood was in several ways unusual. You can read the bare facts on his Wiki article. Duncan was a precocious child, who grew up in an atmosphere of seances, meetings of the Hermetic Brotherhood. Books in the home included the Occult. The household was permeated with Theosophical notions and practice. His deep memory of the mysteries of religion and philosophy, encountered at an early age, were intimately bound up in the organic birth and growth of his consciousness, and, later, his sexual awakening and sense of identity. Duncan tended to see the development of his sense of his place in the world as pre-ordained or destined; and his work serves as a kind of exploration of the structure of that ordination, as an unfolding drama of his own connection to the larger forces at work in the universe. Formally, his work seems to flow out of the Romantics--Shelley, Blake, for instance--though he thought of his work as emerging from the Modernist tradition of Eliot, Pound, H.D., Zukofsky. To the ordinary reader, his work will always seem superficially to harken back to an earlier epoch, pre-scientific and mystical, even primitive. Duncan himself was well aware of these apparent contradictions, and sought to reconcile them in his work.

This poem struck an immediate chord in me when I first read it, not because it spoke to any philosophical issue or ontological preoccupation, but because it addressed what I regard as a universal fact of human consciousness, the sense of conceptual uniformity of existence, a sense which many people have from an early age, often associated with their earliest experiences of reading, though there are other kinds of experience which may offer similar kinds of apprehension of wholeness, or oneness, or unity of being.

Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow

as if it were a scene made-up by the mind,

that is not mine, but is a made place,

that is mine, it is so near to the heart,

an eternal pasture folded in all thought

so that there is a hall therein

that is a made place, created by light

wherefrom the shadows that are forms fall.

Wherefrom fall all architectures I am

I say are likenesses of the First Beloved

whose flowers are flames lit to the Lady.

She it is Queen Under The Hill

whose hosts are a disturbance of words within words

that is a field folded.

It is only a dream of the grass blowing

east against the source of the sun

in an hour before the sun’s going down

whose secret we see in a children’s game

of ring a round of roses told.

Often I am permitted to return to a meadow

as if it were a given property of the mind

that certain bounds hold against chaos,

that is a place of first permission,

everlasting omen of what is.

The meadow, for me, as a symbol or scene of "the made place" is a safe, contained enclosure, within which inquiry, play, discovery and attention can occur. One is "permitted" to return to it, at any time, to the delight and mystery of the world which reading (the portal) reveals. The meadow is then "an eternal pasture folded in all thought." This suggests that the mind itself is the meadow, where this folding takes place--in the same way that earth is turned and cultivated. The folding and enfolding suggests the wrapping and re-wrapping, the turning and mixing and churning of thought itself. The meadow is a sacred place, sacrosanct and inviolable, yet complex and convoluted. Inside the pasture (or meadow) is a hall, inside an "architecture"--perhaps the architecture of the memory and experience of the speaker. Nested inside this architectural space, appear the First Beloved, beholden to "the Lady" who is "Queen Under The Hill""whose hosts are a disturbance of words within words/that is a field folded." This female figure stands over the shadowy scene, "a disturbance of words within words/that is a field folded." The "words within words" (an etymological hall of mirrors?) is a metaphor for the mystery of appearances, and the deceptive, endlessly intriguing maze that is language, weaving spells and conjuring ghosts and expanding boundaries of understanding and awareness. This female figure stands as a kind of guardian over the meadow (or field), though what her design may be, or what she stands for, is unspecified.

And yet, "it is only a dream" made by the imagination, "grass blowing east against the source of the sun in an hour before the sun's going down." Sunset, "whose secret we see in a children's game of ring a round of roses told." The nursery rhyme--an echo perhaps of T.S. Eliot's garden paradox in "Burnt Norton" [Four Quartets, 1935]--evokes the musical trance of innocence locked in the past, forever stuck in the circularity of familiar repetition, of history repeated, enacted, re-enacted.

"Often I am permitted to return to a meadow/as if it were a given property of the mind." And indeed, it seems that the return to the meadow, through the portal or medium of language, is permitted as often as we wish, to recapture its reassuring sanctuary against "chaos""that is a place of first permission"--our original innocence, or our earliest memories of the magic spell wound inside our minds through the alchemy of the incantation (the grammar of consciousness).

The symbolic significance of the First Beloved, the Lady, the Queen Under the Hill, is kept intentionally vague, I suspect, since Duncan wasn't willing to be more specific about the ultimate meaning of these symbolic references. They could be religious references, from Christianity, or more obscure deistic sources. But it seems less important to the poem's meaning and power--than that they remain as expedient figures in the speaker's own hierarchy of personification. Each reader may have a different version of the specific archetypes from the "meadow" of childhood reading and experience. We all bring our own baggage to the poem. Each of us may have our own particular First Beloved, our own Lady, our own secular deity. But our earliest experiences of language comprise a nearly universal participation--a shared recognition that is more, or less, powerful depending upon how keenly it was felt.

Every time I begin a poem, or a novel, or a short story--and the same holds true of musical or video works--I have this familiar settling in, a participation in a process whose magic is as dependable and satisfying as going to sleep, or eating a good meal, or having an interesting conversation, or a walk in the woods, or making love to another. Reading itself is one of the arts, as surely as drawing a picture, or hand-writing a letter. We participate in a process which we are permitted to join. And that permission is our birthright as humans, our capacity to use language, an invitation and a timeless welcome.

↧

Growth - Who Needs It?

In yesterday's San Francisco Chronicle, the lead Editorial was devoted to California Governor Jerrys Brown's proposal to "streamline the approval process for certain kinds of new housing development." His plan "would make it easier and faster to build new housing in California . . . [and] would ease [my emphasis] the state housing crisis." (Predictably, the editorial praised Brown for his practicality and good sense.)

The so-called "housing crisis" is a well-identified phenomenon. It occurs whenever there are more people looking for a place to live, than there are places to live, in a given region. One of the consequences of rapid growth, is housing shortages. Its manifestations are various: Rising prices for homes, rentals, and also homelessness. It affects society at all levels.

In California, we've been dealing with growth for over a century and a half. Indeed, "growth" has become the sacred cow, the holy grail, the third rail, the untouchable concept. Like "diversity," it's become politically dangerous to address, even to mention. Questioning the wisdom of uncontrolled, chaotic "growth" has become as politically incorrect as questioning the value of "multi-cultural diversity."

California Bay Area satellite image, showing urbanization as grey color

On the Eastern Seaboard, or in the Midwest, "mature" settlement has largely moderated, except in Florida. But in the Greater West, we're still experiencing the "open range" mentality, with constant calls for expansion and encroachment, upgrades and enhancements. We're admonished for not building and adding-on and accommodating further additional growth.

After a century and a half of this, we've become inured to the message. Most people don't even question the need for growth, the ever-demanding and insistent cry for "more!" Always more: More people, more roads and freeways, more schools, more police, more sewage treatment, more water, more parks, more jobs--it almost seems at times that it doesn't matter what it is, if it's "more" then we should need it.

But more growth has consequences. More growth means more government, more crowding, more noise, more pollution, more ecological devastation, and--over time--higher prices for everything, as well as shortages of some things that are finite, limited, or irreplaceable. Politicians, contractors, developers, entrepreneurs, and minority advocates all love growth, because it expands their territory, and lines their pockets.

I once had a friend who said, "everyone wants to live in California," and it's true. There's an overwhelming urge to migrate to the Golden State. We have space, good weather, and relative prosperity.

The debate over uncontrolled growth in California will continue, and we can expect to hear the same tired arguments trotted out with predictable passion and persistence, in favor of more housing, more transportation infrastructure, more jobs, more, more, more, more.

But the plain and obvious fact is that California has become--is, in fact, already--a mature region, occupied, filled-up, full. The high price of housing, and the scarce rental market, are symptoms of a disease, the disease of excess growth, and excess population. Ironically, the very things which people think they'll enjoy once they migrate here, are destroyed by this process.

We've all heard about the "flight to the suburbs" which occurred after World War II. There's also the flight to new developing regions, such as the Southwest, where suburban sprawl has been spreading like wildfire.

Scottsdale, Arizona

Henderson, Nevada

The plain and obvious fact about our regional population abstract is that quality of life is compromised whenever "growth" is pursued and designed without regard for the real consequences.

We know that the earth isn't--never was, really--just a playground for human exploitation. There may be no inherent ethical quality about ecological balance, of moderate habitation; but we know what the consequences are when a species explodes. Our instincts tell us that birth is good, that the pursuit of happiness is a human "right" and that democracy is about letting people chase their dreams. But our dreams cannot dictate how we approach common sense problems in the real world.

How crowded do we want our cities to be? How much suburban growth is "enough"? How much blacktop and concrete do we want to spread over the earth? How much natural resource can we justify exploiting for our own convenience? How many species must be sacrificed to extinction to feed our bottomless rapacity?

Jerry Brown says he wants to "ease" the housing crisis by making it more easy to build new houses and apartments. He wants to "include""affordable" housing in the equation. How noble.

And how corrupt!

The bottom line is that as housing prices and scarcity rise, the desirability of migration declines. That arithmetic is easy to understand. We can "encourage" means by which the continuing influx of newcomers can be "accommodated," or we can celebrate the arrival of limits and barriers which moderate growth.

Growth can be a very bad thing, and trying to facilitate additional growth by "helping" the housing market isn't a smart response to the problem. The intelligent response is to acknowledge the underlying causes of "shortages" and address the causes, not the symptoms. The cause of high prices and scarcity is growth itself, not some logistical problem with permits or environmental obstructionists. Because those too are symptoms--symptoms of the outer limits of our tolerance, and the region's natural holding capacity. Our recent "drought"--which may have been brought on by global warming--is another symptom of the finite limits of the region. There's no reason to think that short-term, short-sighted "fixes" will ultimately solve the problems of excess growth.

Jerry Brown, who once stood for reasonable intelligent public policy, now advocates unlimited growth. Speed trains along our coast, more "canals" to divert water, and now, streamlined housing construction. He no longer questions the growth paradigm. He says he wants to address global warming, but his solutions actually will exacerbate the problem, by directly stimulating the underlying causes of climate change.

He's been body-snatched, and now marches to the old music.

↧

↧

Arsenic / Absinthe in the Limelight - Green in the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec [1864-1901] seems almost like a figure from mythology. You couldn't make up a person like that, except perhaps as a figure in a French fairy tale. Physically deformed from an early age--legs stunted so that he never exceeded 4' 8" in height--he managed to create an unique body of stunning work in just a few short years, before succumbing to the effects of alcoholism and syphilis.

As a painter, Lautrec occupies a crucial position in the history of art, just after the ascendancy of Impressionism, but before the great iconoclastic convulsions of Modernism (pointillism, cubism, futurism, Dada, constructivism, etc.). His work is frankly representational, but infused with special qualities and innovative effects. His subject was Paris night-life, the garish watering holes of the well-to-do, as well as the brothels and circuses and bohemian quarter.

Though high-born, with means, his physical deformity meant that the social circles of respectable class were closed to him, so he fell in with the lower elements with which he came to identify.

Nearly everyone is familiar with his raffish poster designs, the nudes and dancers and candid vignettes. They recreate a fin-de-siecle Paris world, decadent, dilettantish, gestural, piquant, forsaken, sad, vicarious, naughty.

There are many ways to approach Lautrec's art. In it are aspects of exhibitionism, degeneracy, burlesque, casual malignity--all of which Lautrec portrays with a directness which belies his shrewd sympathetic regard. The figures in his art, though often seemingly lost to virtue, are interesting, intriguing, enmeshed in a closed world of sexual longing, frustration, and occasional bacchanalian abandon. Indulgence seems its underlying motive-force, with the predictable aftermath of boredom, fatigue and shame.

One of the chief aspects of this transgressive atmosphere in Lautrec's use of color to shade meaning and spin aura is the subtle application of the color green. The more I've looked at Lautrec's work lately, the more noticeable this aspect seems.

Lautrec was known to favor absinthe, the spirit liqueur which was once thought to generate hallucinations and visions, but which recent science has proven to be a myth. Nevertheless, artists and bohemians in late 19th Century Europe popularized the notion that the "green fairy" could seduce imbibers into a deadly addiction. Absinthe became a late romantic indulgence, hence its appearance in Lautrec's paintings of Paris cabaret and bistro culture.

Absinthe appears frequently in the paintings, and its potent green color acquires a symbolic reference, a code for the dissolution and decadence of the epoch. The more you look at Lautrec's work, the more you notice this green tint, not just in representations of clothing, or decor, but around the edges of things, in the shadows, or in the outlines of figures or objects.

The more you look, the more you see that many of Lautrec's paintings are virtually immersed in a shimmering, evanescent pale, lurid green numinosity, which signals the influence of mortality and cultivated decay. Sometimes it's obvious, other times more subtle.

One of the revolutionary elements of Modern Art is its counter-intuitive use of color, an aspect that became like a signature of the new style at the turn of the last century. We would expect that Lautrec, like Cezanne or Matisse or Monet, would use combinations and contrasts that challenge our assumptions about the actual appearance of hue; but in many of Lautrec's paintings, green doesn't just appear, innocently, as a delight and titillation to the eye. It has an explicit, subconscious presence.

Ask yourself, looking at the painting above, what the purpose of all that green on the sheets and faces and pillows is? It almost seems a kind of ethereal plasm which covers everything in the scene.

Ordinarily, we would say that the use of convergent, even clashing colors in a modernist composition is evidence of the panchromatic argument about the complexity of our apprehension of light, and how painters will play with that notion to achieve various effects. But in these works, it seems more an intention--conscious or not--