As a young artist, Wayne Thibaud worked as a cartoonist and commercial illustrator, during a time when such media were not considered serious art. They were illustration, popular consumer fare, unworthy of critical regard. Like the Pulps, Comix, Dime Novels, and cinema serials and cartoons, commercial artistic work was a bargain artists might strike with necessity, something they did to make a buck. Serious art belonged in galleries, not on newsstands or up on billboards.

Thibaud, of course, was one of the early progenitors of Pop Art, the movement which legitimated our interest in cartoons and comix and pulp. Framed inside the conceptual limit of "serious" representation, Thibaud and his contemporaries (such as Warhol, Lichtenstein, and Wesselmann) turned the art world on its head, foregrounding and celebrating the symbols and commodities of our capitalist mass cultural picnic, bringing the techniques and tricks of illustration and cartoons directly into play in the elite sphere of collectible, traditional art.

Though Thibaud spearheaded the Pop movement in the 1960's, his deeper preoccupations would be revealed in his portraits and figure studies which paralleled his inanimate object images. One of the problems of Pop style is the typical way that human figures are rendered as typecast or stereotypes, lacking human character and ambiguity. (It seems that in art, the more emotional ambiguity one can get into a human face, the better.) Thibaud's very unique character and figure portraits exhibit a specific segment of regard, neither highly individualized, nor general--adrift in a sort of middle ground between actual existence, and an artistic limbo.

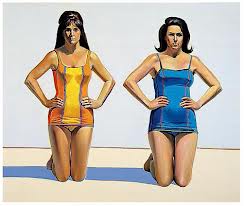

These two women seem to refer to specific models, and may well have been painted "from life"--but there's a generic quality which tends to deflect that specificity into a more stereotypical realm. They become "examples" of type, rather than studies of individual people. The composition is abstract, because it (typically) has no background, no context. I suppose it could be in an indoor swimming facility, or at the edge of some kind of drop-off, but it's clearly intended to portray two women completely divorced from any reference--two generic "types" set adrift in a three-dimensional void.

The second pair has the same existential presence--two people possibly related, or not--sitting in poses of slightly impatient boredom. Late mid-century citizens--certainly American--posing for the painter. Yet their identity seems indeterminate. They could be friends of the painter, or just casual acquaintances who agreed to pose, probably for free. They aren't "artist's models" in that sense, just "ordinary" people, intelligent, alert, and slightly distracted. But, again, they have no attachment, and it's that disengagement, that slightly anxious disconnection that provides the whole point of the painting. If they're meant to stand as victims of the painter's regard, we're powerless to save them. They're caught forever in this attitude of mild delay, a circumstance either so common as to be incidental, or so forlorn as to be tragic. But the picture answers none of these speculations; it sits at the edge of statement, cool, distanced, stuck in its own groove.

In one of Thibaud's signature images, a youthful woman wearing a full bathing suit, sits facing the viewer, holding a pink ice-cream cone to her mouth. She looks as if she is perhaps by a swimming pool, or near the ocean. She's completely relaxed, and unself-conscious, but there is a look of slight concern on her face, as if she's just noticed something slightly unexpected or worrisome. Her legs are spread, revealing the blue patch of trunks at her crotch. At one level, the pose isn't especially revealing or suggestive, but there's an aura of complete disorientation. The light source "behaves" like sunlight, but there are no visual queues to support that presumption. Like the other Thibaud figures, this model exists in a kind of spatial purgatory, neither really "in" the world, nor out of it.

In the context of the sensual attractions of the artist's rich food and dessert studies, the woman projects an obvious sexual innuendo. She's both the unwitting sacrificial "victim" of the artist's appropriation, and a neutral participant in the symbolic position she occupies. The pairing of the ice-cream cone, and her spread legs, are obvious codes for sexual meaning. But the overall mood is so bland and relaxed--as if we were on vacation from the "serious" side of daily insinuations--that we're free to experience the portrait as an innocent occurrence, cleansed of any guilty reservations we might have about looking.

The picture seems a perfect summarization of the attitude of the liberated 1960's--of the craving for release and permission, of a license to feel, even at the expense of respectability or grace. "You can have it all," the picture seems to be saying, at least on one level, you can devour and embrace material pleasure and possess prizes without any loss of dignity. Yet on another level it's a denial of fulfillment. Her feet, raised towards us, seem to be poised to push us away. Her arm, supporting her from behind, prevents her from bending back in a position of released posture.

She isn't really interested in us--she's eating her ice-cream and is looking elsewhere, at something, or someone, past us on the right side of the illusionistic space. That distraction is a familiar position in Thibaud's portraits, of the separation of viewer and subject. His people don't care about being portrayed, they're unexcited about the prospect. The candidness, say, of photographic shots, doesn't apply here. "Okay, take your picture' or "hurry up and finish the painting, my arm is tired; it's hot out here!" Despite its obvious symbolic suggestiveness, the painting is flat, suspended in a timeless emptiness within the frame of the canvas. Unlike a snapshot of someone in exactly this pose, this doesn't capture anything; it's more formal than that. Try as we might, we can't put this woman anywhere--she doesn't fit into any narrative or setting that would legitimate our interest. She's without history, nameless, without a past and or a future.

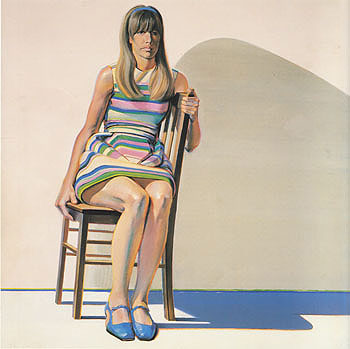

The cold finality of these portraits, their edgy refusal to connect with any purposeful or emotional ulteriority, can be distancing. The young woman's attitude of leaning against the chair's angle pushes the perspective off-balance, an unresolved visual conundrum. Who is she, and why is she sitting in this chair, sideways, in a slightly rigid, slightly defensive way? She seems a little uncomfortable, and so do we. Her cheerful dress does nothing to relieve this tension. And that impossible, unarticulated shadow behind her just adds to the mystery. She holds her knees chastely together, but there's nothing particularly purposeful about that, either. Feet flat on the floor, together. He face is blank, though particular enough not to seem doll-like. She's not a store-window mannikin, she's a thinking, feeling person. But what is she doing in this twilight zone of space? Can we care about this person, is her fate something we're meant to connect to?

The more we study the painting, the more we see that it's a dance of colors. The blue shadow connects to the blue of her shoes, and the horizontal striping of her dress. There are little shimmers of blue and green on her legs, in her barrette, on her arms, under her chin; tiny strips of red and yellow on her skin. Her legs are white, but her arms are brown. The painting is like a color wheel, a rainbow panoply of application built up out of dense coherences of improbable combination of different light. The closer you look, the more it all breaks up into pixels and points of reflection. Individuality and detail are subsumed into a spectral matrix of detail.

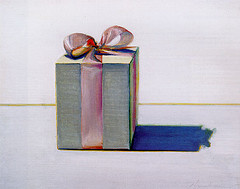

What does art offer us? A picture of reality, or an arrangement of color and form? What is the secret withheld, in the material world, that art can unlock for us, or reveal? This marvelously simple and obvious study of a gift-box--the ideal metaphor of a prize within, waiting to be opened, but withheld from us (because inaccessible) possesses the same poised assurance of the food studies, and the portraits. The box is like an axiom of all Thibaud's art, the sensual embrace with rich surfaces and textures--filled with hunger and thwarted intensity. So in the end you can't "have it all." There's always another box, another painting, another juicy sweet to consume. There will never be an end to the replication of commoditized delight, of desire seduced.

Death may terminate the feast of the eye, the mouth, the skin and nerves, the ear--but the simulacrum endures. A pink bow around a box never opened-- sent by whom?-- meant for whom? Which is what the consumer culture does--makes hungry consumers out of us. And the artistic artifacts are one with the packaged replications of food, clothing, transport, tools, toys--all the stuff that fills our world. Thibaud's canvases share this material immanence, a boundless surfeit of infinite production. Wanting and having. Desiring and possessing.